Suggested citation: Ananayo,Z.(2009). Rice Terrace Construction and Maintenance. Nurturing Indigenous Knowledge Experts among the younger generations, Phase 3. nikeprogramme.net. https://nikeprogramme.net/?p=364

For the Ifugao, the primary purpose in constructing a ricefield is for agricultural production. Due to sheer necessity for food, they painstaikingly carved rugged mountainous terrain to make terraced pond fields for rice cultivation. Despite lack of formal training and technology, Ifugao forebears turned hills and mountains into magnificent rice terraces fortified by enduring stonewalls that were made productive by ample supply of water through intricate irrigation systems.

Over the years, the product of the people’s resourcefulness has become well known especially with the amplification of its aesthetic, archeological, engineering, architectural, and socio-cultural significance.

Indigenous Approach To Rice Terrace Building And Maintenance

The Ifugao approaches terrace building with respect to the agricultural cycle. By evaluating the topography, vegetation, water resource, and availability of building materials, he plans the land use, irrigation and drainage channeling, and work phasing in July to October bearing in mind to finish the construction in time for the planting season in November to early December (Guimbatan, 2003).

Because water supply is very much needed during and after the construction of a ricefield, it is the main consideration when selecting a construction site. The indigenous rice variety (Tinawon) requires that the field be inundated throughout the cropping season just as the pondfield needs to be filled with water the whole year round to stabilize the slopes or to prevent erosion.

Soil type should also be suited for rice production. In the Kiangan area, farmers prefer two types of soil, namely: clay (pidot) and loam (mahalibukag). Furthermore, the terrain is also considered as this affects the ease of construction and maintaining the paddy. For instance, very steep slopes are very vulnerable to landslides and render it difficult to clean its walls. The terrain also affects the area of the paddy. It is observed that where the slopes are steep, the paddies are narrower and where the slopes are gentler, the paddies are wider (Buyuccan, 2009).

Unfinished construction work and repair are done quickly in the early planting season when the seedlings are prepared for transplanting. Thereafter, irrigations are maintained and terraces are guarded from possible erosion from the planting season to harvest season. Eroded terrace parts and slumps caused by sudden rainstorms are only repaired after harvest season. After harvest, evaluations begin again and the cycle continues.

Engineering Principles In Rice Terrace Construction

Engineering techniques are used in constructing and reconstructing the rice terraces. These methods were developed in observance of water behavior and soil consistency.

1. Site Selection

Pondfields are usually constructed where the natural incline is least and where sufficient water supply and other essential materials are available. In U-shaped valleys, terrace building begins at the lower elevations near the main channels of the drainage basin. In V-shaped valleys, terrace construction takes place in areas with gradually inclined slopes (Conklin,1980:16).

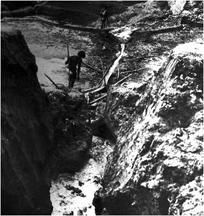

Hydraulicking refers to the method of sluicing (bulubul or budubud) fill materials such as soil, gravel, stones, and rocks from an upper elevation to a pond field below with the use of strong water force. The soil is used by the receiving pond field either as fill material or topsoil. Apart from terrace formation, hydraulicking is done to widen ricefields and to clear erosion or landslides which has fallen on the pond field. Sluicing earth and rock as a method of backfilling the stonewalls ensures that the constructed wall is bonded together by the finest material (Guimbatan, 2003).

2. Hydraulicking

The process entails the creation of a pond at a higher level where water is impounded. Then, temporary channels from the site are constructed, sometimes passing across other pondfields, leading to the pondfield below so that the materials are guided to where it is needed when water is released. Usually, hydraulicking is done during off season, from July to September, at the height of the rainy season. If rainfall is insufficient, irrigation and drainage water may be diverted to have enough water for sluicing.

3. Retaining Walls

There are two types of terrace walling practiced by Ifugao farmers, the stone-walled (tuping) and mud-walled such as the clay type (mim-i) or those following the natural slopes of the hill or mountain.

Where the slopes are steep, farmers build stone walls to protect and strengthen the terrace walls. Conversely, areas with gradual slopes and rich in clayey soil make use of earthen walls. While these are easily washed out during the rainy season, they are easily restored through a method of soil tamping that sometimes reshape the terrace ponds. In Mayoyao, all rice fields are stonewalled whereas, in Kiangan, Hingyon, Banaue, and Hungduan, both mud and stone walls are utilized. Stonewalls are best constructed during dry season. It has been observed that stonewalls constructed during rainy season collapse easily because the soil is loose.

4. Random Bonding

Preferred stones have different shapes with regular size. Only big ones are used for foundation or placed at the boundary to serve as a marker. Small stones, wedges, and chinking stones are used with stones of different sizes thereby ensuring a tight bond.

Except for the two foundation stones, random bonding is employed in stone walling. As fill is sluiced in and leveled behind the gradually rising masonry, each stone is carefully laid in its best tilted position to avoid unbounded alignments. Larger rocks are placed lower in the wall than smaller ones. Where angular and rounded stones must be used, the angular elements must be used first. Angular and irregularly shaped stones allow for more contacts between elements and ensure greater stability under conditions of weathering, seepage, and ground movement due to earthquakes (Conklin, 1980:19).

Subrounded and oblongish stones are laid so that they tilt back into the terrace body with the heavier and somewhat higher end facing out. In contrast, flat stones are set up on their sides so that their longer cross-sectional dimension is placed more or less vertically. They are also used as sills for spillways. For individual stones with a longer dimension, they are laid more often as headers than as stretchers. This helps to develop transverse strength through the wall (Conklin, 1980:19).

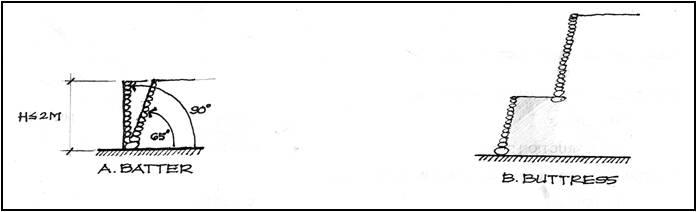

5. Buttressing

In buttressing, the stonewall is supported or reinforced by building a counterfort or a projection from the original wall. As observed by Conklin (1980) in his study areas in Banaue, the average height of main sections of stonewalls runs about two meters to six meters if there are no buttresses.

Conklin clarified that the batter of terraced stone walls depends on a number of features, the most important of which is the size of building stones. With very few exceptions, walls tilt at angles from 65 to 90 degrees. In addition, the shape or profile of the terrace wall is also important. A straight incline or a slightly concave batter is desirable. Conversely, deviations from this type of profile are signs of a badly filled or poorly constructed embankment.

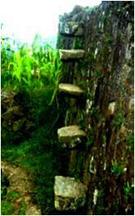

The purpose of sloped stonewalls and buttressing is to counteract the overturning moment made by active soil pressure. Bigger stone foundations are set to resist slipping at the base and a building technique is employed to bond materials together for structural strength (Guimbatan, 2003). Jutting header stones are sometimes built into steep walls to allow for climbing from one level to the next. Stones or logs may also be set in high walls for women to stand on when weeding.

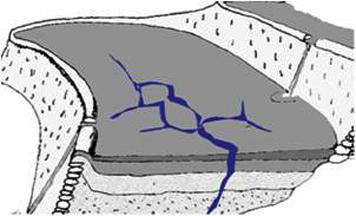

6. Water sealing

Illustration: Rachel Guimbatan, 2003

Water seepage into the foundation line of the slope may lead to a landslide thereby causing serious damage to the rice pond. To prevent this, moistness and plasticity of the pond bed must be maintained the whole year round. During dry season when water is scarce and cracks (okak) appear at the top soil layer, water is sometimes gently poured over the cracks thereby making the soil expand and sealing the pond bed. A crawling grass with furry leaves (il-ilit or il-li il-li) may also be spread over the dike and wall surface to protect the areas from direct sunlight (Guimbatan, 2003).

7. Irrigation and Drainage System

A carefully laid-out irrigation and drainage system is required to ensure that water is available all year round for the paddies and the rice crops. The entire system depends on gravity. As Conklin (1957), Guimbatan (2003), Buyuccan (2009) illustrated, water from springs (otbol, ofob), creeks (wa’el), river (wangwang) are generally diverted and dammed in an impounding area (putut or paluk) before distribution to the different ricefields by means of artificial irrigation channels (alak) and water conveyor troughs ( tulalok/huyung).

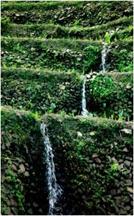

There are three general principles being observed by farmers in water management: heavy flow of water must be diverted from the terraces; entry of water to the pond fields must be gradual; and inundation must be maintained at all times (Guimbatan, 2003). To protect the slopes from eroding, the hydraulic system in the rice terraces is designed in a manner whereby water channels are carefully laid out in recognition of the natural courses of water runoff and its velocity regulated by the angle of its conveyors. In irrigating the terraces, the principle is to reduce the water force as it enters the pond field. The entry of water into the rice paddies is regulated by attenuation and this is achieved through an almost horizontal layouting. This way, water gradually moves along irrigation canals that are either carved out of the mountain sides or through makeshift conveyors.

Photo: Marlon M. Martin

Flooding in the pond fields is balanced by constant maintenance of the spillways (guhing). Excess water from a higher ricefield is drained to the lower paddy or to a nearby creek through the spillways. During rainy season, exit of water from the pondfield is done by expanding the spillway. On the other hand, the spillways are closed especially during dry season to prevent water loss. To divert the flow of an otherwise destructive heavy volume of water, excess water from the irrigation source, natural drainage, and spillways, is directed to a channel (gohang, liglig). The walls of the channel are self-standing and designed to withstand water velocity. In contrast to the principle of irrigation, the water flow of the drain channel travels the shortest distance possible from the top to the river below.

Building A Stonewall

Among the tools commonly used in rice terrace building are spade (gaud), crow bar (dohag/balita), and bolo. Wooden pestles are also used especially in tamping soil or clay during back-filling of stonewalls and dike construction. On the other hand, building materials are composed of stones, rocks and soil. Two kinds of stone are used on terraced walls. One is fired, split sandstone (piningping, pinhi’) from big boulders of rocks and the other is river-washed cobblestone (muling).

One stone is systematically installed on top of the other with the use of soil and small stones as bonding and fill materials. Soil bonding principles are observed when restoring eroded earthen walls or repairing cracked walls. The restorations always start by excavating the damage up to the portion unaffected by the cracks. Restoration methods are applied according to the condition of the damage (Guimbatan, 2003).

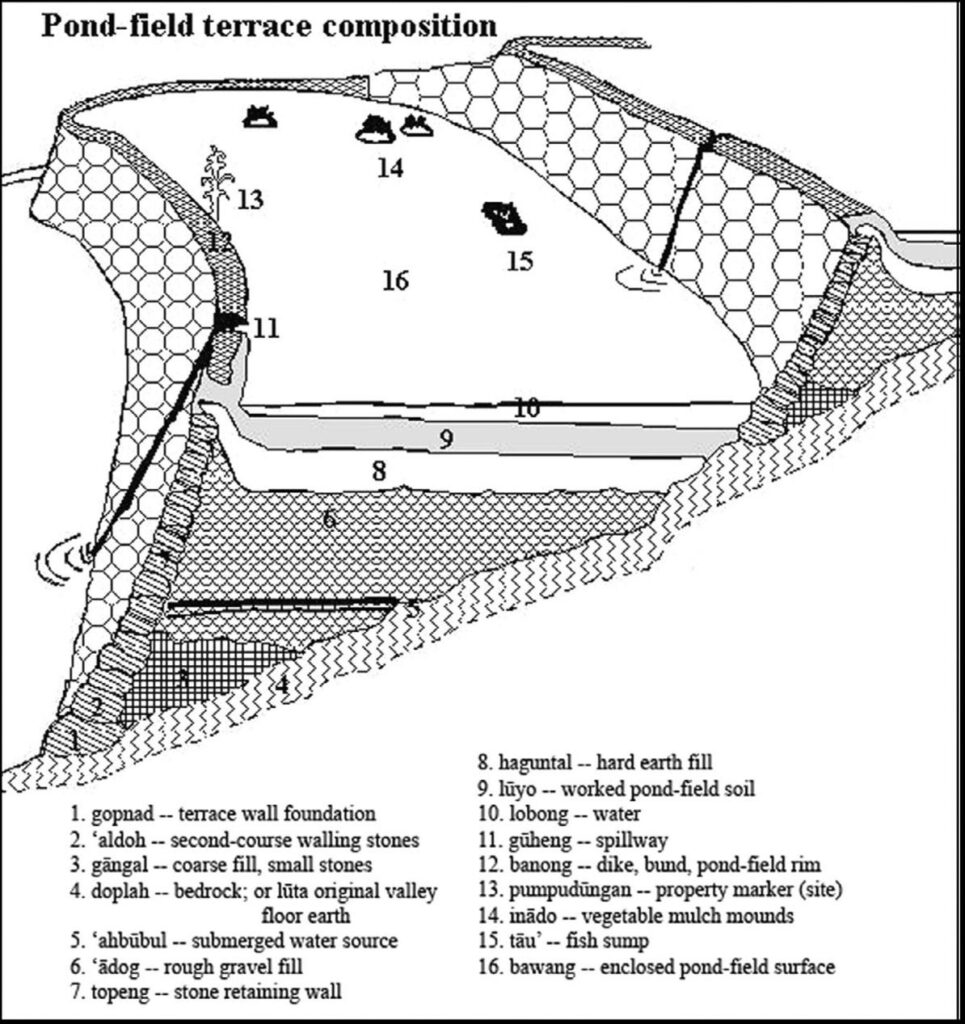

Stonewalling and Backfilling: Tuping and Tabab

The foundation stone (gopnad/dalinat) is laid on the excavated slope and filled back with soil. The second stone (aldoh) is laid on top of the foundation stone followed by subsequent layers of soil. Angular stones of longer dimensions are laid as headers. This helps develop transverse strength through the wall. On the other hand, elongated stones are laid tilting back into the terrace body with the heavier and higher end facing out (Guimbatan, 2003).

The stones are filled with soil and tamped with a wooden pole or a pestle to make it compact. Wedges and chinking stones are also generously used as fillers (tabab). The care with which terrace fill is packed behind each vertical rise of stone walling contributes heavily to the lasting quality of such workmanship.

Photo: Jovel Francis P. Ananayo

Photo: Teresa P. Aliguyon, 2010

Photo: Save the Ifugao Terraces Movement

Photo: Ifugao Cultural Heritage Office

Photo: Save the Ifugao Terraces Movement

When the desired height of the stone wall is reached, backfiling and tamping are done vigorously until the soil is dense to make a hard earth fill (haguntal).

The area is leveled and the terrace bed is filled with soft and thoroughly worked clayey topsoil (luyok) to a depth of at least 20–30 centimeters. The clayey surface is smoothened and inclined slightly downward toward the uphill side margin to safeguard the loss of pond water (Guimbatan, 2003).

A dike is constructed at the outer rim of the rice paddy. This is done by laying of soil to build the bund, moistening the bund, and plastering the bund with clayey soil with a paddle spade and then pressing it into place by the heel of the foot. In drier terraces, the outer margin may be drained for the seal at the rim to be pounded with wooden pestles (Conklin, 1980:19).

If sufficient clay is available, the clay is thickly plastered on the top and sides of the dike with paddle spade and pressed into place with rapid foot action. This coating helps reduce water seepage, retard weed growth on the dike, and raise the dike to the desired level (Conklin:1980:19). Dikes are provided with at least one spillway each. Then, the pond is filled with water. Some of the dikes that are used as heavily traveled footpaths are overlaid with stepping stones.

Photo: Rachel Guimbatan, 2009

Photo: Zenia B. Ananayo

Photo: Marlon M. Martin

Maintenance And Repair

For general hydraulic control as well as prevention of excessive runoff and erosion, terrace owners stress the importance of preserving watershed forest cover (Conklin: 1980:30). Clearly, they understand the adverse effect of subsequent drying up of surface and irrigation water once excessive tree cutting is done.

1. Seepage Prevention

To prevent seepage within the pond bed or at the dike, farmers make sure that the clayey soil of the pond bed is maintained in a wet muddy condition throughout the year. When there is a crack in the pond bed, it is packed with moist soil or clay until the crack is sealed.

Excessive seepage due to remarkable weakening of the retaining capacity of dikes, pond bed, terrace walls, and embankments caused by earthworms may lead to destructive slumping and washouts. To prevent recurrence, coarse gravel and broken shale fill is substituted for the earthen layer just beneath the outer sections of muddy soil and against the upper part of the terrace rim and dike. However, if worm-caused seepage increases alarmingly during the dry season, a temporary mud dike may be formed a few meters back from the bund to prevent further loss of irrigation water (Conklin, 1980:30).

2. Repair of Eroded Retaining Walls

Photo: Zenia B. Ananayo

Repairs that will not adversely affect the crops may be done immediately. However, repair of most landslides and washouts are accomplished only after harvest season since they require sluicing of unwanted silt and debris as well as piling slumped walling stones, fill, and topsoil separately for rebuilding, removal, or possible return to the original level (Conklin, 1980:29).

The following are methods of repairing soil wall erosions (Guimbatan, 2003):

Mim-i Method in Kiangan

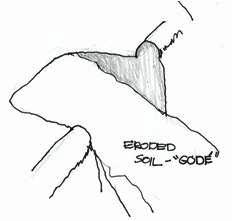

The mim-i method is done if a section of the soil wall erodes (gode). Using the same soil material, it applies the principles of soil bonding and improved technique.

- Excavating the eroded portion until the foundation stones are exposed.

- Curing excavated soil by keeping it moist.

- Layering of spadefuls of moist soil in an interlocking manner (munkikinallatan) on the excavated portion.

- Tamping after each layer to make the soil dense, followed by another layer of interlocked soil.

- The process of soil layering and heel tamping continues until compacted soil reaches the desired height.

Illustration: Rachel Guimbatan, 2003

Illustration: Rachel Guimbatan, 2003

Hodhod Method in Kiangan Area

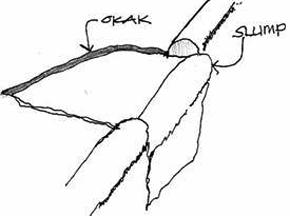

The hodhod repair method is done if there a slump on the soil wall due to cracking (okak):

- Excavating the pond bed beyond the end of the crack. The protruding slumped portion remains as a molder.

- Laying of thin layers of backfill (cured excavated soil) followed by heel tamping. The layering and compacting continues until it levels with the pond bed. The slumped portion remains and acts as a molder for the compacted soil.

- Scraping the protruding slumped portion of the terrace wall until it is aligned with the rest of the wall. This is done through quick diagonal downward strokes alternately applied on both ends of the slumped soil. Scraped soil can be spread evenly on the pond field below or added to the backfill.

Illustration: Rachel Guimbatan, 2003

Illustrations: Rachel Guimbatan, 2003

Labor

In the earlier days, Conklin (1980) noticed that a standard unit in stone wall construction measures approximately two (2) meters high and four (4) meters long which is roughly equivalent to five (5) man days of labor and 25 bundles of rice repayment. He further noted that an important condition under such contractual arrangements is that the new wall must stand up through the following harvest. If it does not, it must be rebuilt in the next off season without additional remuneration.

Construction and repair of waterworks is the responsibility of farmers whose properties may be affected inasmuch as spring, irrigation, and drainage channels are not privately owned. The owner of the largest pond field may initiate the organization of labor and provide the food of the work force.

Other modes of labor include the payment of daily wages for each of the workers which are agreed by both the owner and the workers before work commences. Usually, it is the daily wage in the area. The agreement also includes whether food will be provided by the terrace owner or if the workers will bring their own food. In this case, the daily wage is adjusted accordingly. Another mode is the ubbu system where the workers agree to work for each other’s field for similar terrace works for the same duration of time (Buyuccan, 2009).

Rituals

Rituals are performed before the construction to gain the favor of the deities so that no accidents may be encountered by the workers until the work is completed. Usually, such rituals are performed at the worksite. After widening a rice field through hydraulicking, the farmers in Hingyon peform the ritual halangan to thank the deities for the successful completion of the work as well as a prayer is offered so that it may endure destruction and become productive (Buyuccan, 2009).

In Banaue, whenever a new terrace or major construction job has been completed, a contingent rite (ulpin di p’aagaud) is performed at the embankment near the outlet spillway to celebrate the achievement as well as to ensure its permanence. The entire rite including the sacrifice of at least one chicken takes place at the field site. (Conklin,1980:19).

Meanwhile, in Kiangan, the langlangan ritual is performed after the construction of a stonewall. Seven chickens are butchered. During this rite, the owner of the ricefiled plants either an atolba, bagu, or laglagim tree on the terrace site to make the ricefield more abundant (Buyuccan, 2009).

Customary Laws

1. Water Distribution

The water in an irrigation channel does not belong to anyone. When water to pond fields are directly supplied by streams and other natural channels, those nearest to the channel can always access water supply. Meanwhile, pond fields supplied by artificial irrigation channels apply the rights of prior appropriation (Conklin: 1980). For example, “if A, builds an irrigation channel, for his parcel and B later constructs a terrace halfway along the channel, B may tap into the channel by making a payment, usually in pigs, to A and by agreeing to share the upkeep of the channel” (Conklin, 1980:28)

Correspondingly, water which has been flowing to an area of irrigated land may under no circumstances be diverted to irrigate a different area, even though that area be nearer the source of the water. A person who acquires rice fields, one of which is near the source of the water supply and the other at a considerable distance from it, may not pipe or trough the water from the upper field to the lower one if the water has meantime been irrigating an intervening area (Barton, 1919: 61).

2. Irrigation Ditches and Violation of Irrigation Laws

Normally, irrigation ditches are owned by the builders. In a time of great need, one of the builders of an irrigation ditch may sell interest in the ditch. The builders of an irrigation ditch who have sold part of the water from their ditch, must share the water in time of water scarcity with those to whom they have sold, in proportion to the respective areas of the rice fields (Barton’, 1919: 61).

Though the first offense of a malicious destruction of an irrigation ditch or the diversion of water without permission is usually unpunished, repetition of the offense is punishable by fine or even death in some cases.

3. Boundary Disputes

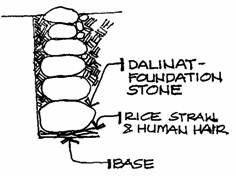

Illustration: Rachel Guimbatan, 2003

Boundary conflicts may arise when a clearly defined boundary line or marker is nonexistent, there is an intentional shifting or removal of boundary markers. Boundary disputes are settled by exposing the foundation stone. In Kiangan and Hungduan, this property line is set by the laying of human hair and rice straw underneath the base stones of the terrace wall. Since rice straw does not rot in airtight surroundings and human hair does not dissipate, the boundary is secure (Guimbatan, 2003).

In addition, trials by ordeal through bultong (wrestling) and uggub (darting) ordeals are commonly utilized. During a wrestling match between the two parties in conflict, the wrestlers need not be the actual persons in conflict, rather, only as representatives of the parties involved. Attempts are made to ensure that opponents are evenly matched so that justice, instead of strength, which is the essence of the match, is achieved. The wrestlers begin the match from one end of the disputed boundary line to the other end. Then, they wrestle again at the midpoint. An umpire facilitates the match. Wherever the wrestlers fall, the umpire drives a peg into the ground beside the left ear of the fallen wrestler. This is to mark the second point of the new boundary line. Stakes are stuck along the line between the first peg and the second peg to form the new permanent boundary.

The ordeal by uggub involves the protagonists throwing runo shoots or eggs at one another. The owners of the rice fields put stakes of runos with leaves along the line on what they conceive to be the correct boundary. Then, by standing at a distance set by the umpire, each takes turn in throwing runo darts or eggs at the back of each other. The one who is hit is declared as the guilty party who wished to move the boundary line; whereas, whoever missed being hit is deemed the innocent party. In case both are hit, a draw is declared and the umpire sets the new boundary usually at the midline of both parties’ claim.

by Zenia B. Ananayo, originally posted in 2009, NIKE programme – NCIP, Phase 3

References

Acabado, Stephen. 2009. A Bayesian Approach to Dating Agricultural Terraces: A Case from the Philippines. Antiquity Journal. Volume: 83 Number: 321 Page: 801–814.

Barton, Roy Franklin. 1919. Ifugao Law. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. Vol. 15, No. 1, Pp. 1-186, February 15, 1919

Buyuccan, Carmelita. Traditional Engineering Techniques in Constructing the Ifugao Rice Terraces. A paper presented during the Inter-Agency Heritage Conservation Workshop to Develop Infrastructure Guidelines for the Ifugao Rice Terraces, March 27, 2008. Hungduan, Ifugao.

Conklin, H.C. 1980. Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao: A Study of Environment, Culture and Society in Northern Luzon. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Guimbatan. Rachel B. Terrace Building Systems and Maintenance Technology: Indigenous Approach vs. Conventional Approach. Paper presented during the 1st Review and Stakeholders’ Workshop on July 21-26,2003 at the Banaue Hotel, Banaue Ifugao.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read something such as this before. So nice to search out somebody with authentic applying for grants this subject. realy i appreciate you for starting this up. this fabulous website are some things that’s needed on the internet, somebody after some bit originality. helpful purpose of bringing new things to your web!